John Lewis is the only person to have spoken at the 1963 March on Washington who is still alive. He was just 23 years old when he addressed the crowd of more than 200,000 at the Lincoln Memorial 50 years ago.

Lewis is a pillar of the civil rights movement. The son of sharecroppers in rural Alabama, he went on to become the president of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and then, eventually, a U.S. congressman from Georgia.

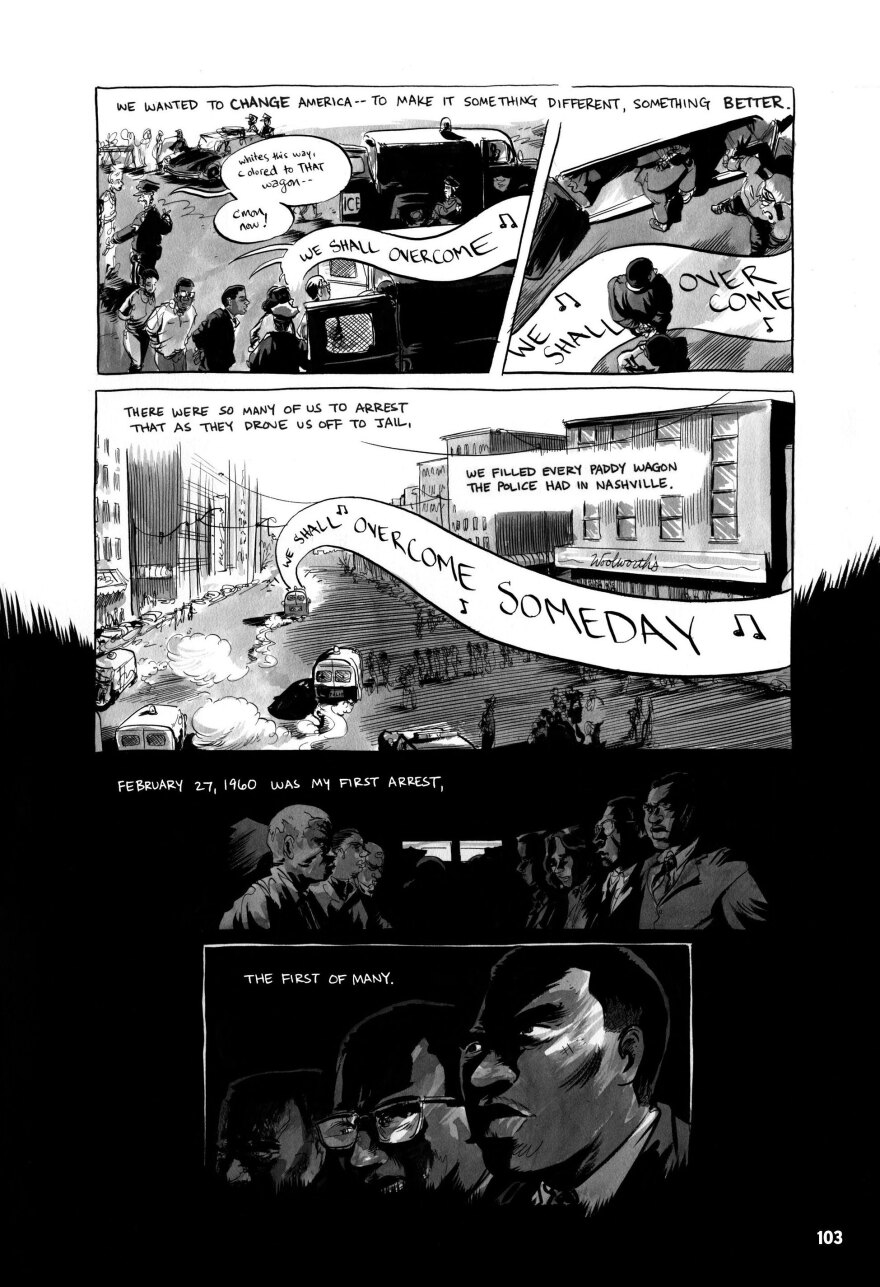

His story has been told before in documentaries and books, but now he's putting his life story into the form of a graphic novel, March. Every superhero has an origin story — and so does the graphic novel of John Lewis' life.

A bunch of staffers on Lewis' 2008 re-election campaign were sitting around, talking about what they would do next, including Andrew Aydin.

"Unashamed, I said I would be going to a comic book convention. And there was a little teasing, but Congressman Lewis stood up for me," recalls Aydin.

Lewis says, "And I just said, 'You shouldn't laugh. At another time in another period there was a comic book called The Montgomery Story ― Martin Luther King Jr. and the Montgomery story — that inspired me."

Imagine a young John Lewis in 1958 — 18 years old — having arrived at college, picking up a comic book. Lewis says the comic tuned him in to a greater story: It tells the story of Rosa Parks' symbolic refusal ― but it also gives a detailed account of how to protest nonviolently. It was a lesson Lewis took to heart when he staged sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Nashville in the late '50s.

"It was on February the 13th, and we had the very first sit-in here. And I took my seat at the counter. I asked the waiter for a hamburger and a Coke," Lewis says in a 1960 NBC documentary.

Lewis' staffer, Aydin, knew the history but didn't know about the old comic book. Aydin became convinced Lewis should tell his story as a graphic novel. But Lewis wasn't so sure.

"I thought he was somewhat out of his mind. Why would I be writing a comic book?" Lewis says.

But then he thought back: "I do remember reading The Montgomery Story comic book, and I said, 'Yes, if you would do it with me.' And it's been a labor of love."

That labor brought them all the way to San Diego's Comic-Con — the geek and supernatural mecca known for its outlandish costumes.

Waiting in line were three Dr. Whos, four Wolverines and one guy in an elaborate Transformers outfit. But they weren't waiting to see the stars from the latest sci-fi movie. Hundreds of people stood in line to have Rep. Lewis sign their copies of March.

Among the Comic-Con fans was Mary Clark, a teacher at San Elijo Middle School in San Marcos, Calif.

"This will go into my library collection," Clark said. "As a graphic novel, sometimes students who aren't really enthusiastic readers will pick it up thinking it's about the pictures, so to be able to give them a story alongside those pictures and something as powerful as Congressman Lewis' story."

That story spanning the congressman's seven decades will be told in three books. March is the first.

It begins with John Lewis as an old man waking on a dark early morning in Washington, D.C. It's 2009, the day of President Obama's inauguration. Quickly the reader is sent back in time ― to Lewis' childhood, when he was taking care of his sharecropper parents' chickens, practicing sermons on the young birds.

The pictures are black and white, and graphic artist Nate Powell renders Lewis' life in shadow. Powell says he drew the story close to the ground, the way a child would experience the world.

"I could simply slip into his shoes for that moment," Powell says, "and I knew precisely what it was like to witness the baptism of these chickens ― the loss of a beloved hen down a well. The hiding under the porch so that he could sneak away from his house in order to get an education each day and hop on the bus, with his mom chasing after him."

The up-close perspective ― sometimes so close you only see what Lewis is seeing ― gives way to wide shots and birds'-eye views as the story shifts to sit-ins and marches. Powell says there were things that were tough to draw.

"Trying to find the appropriate and powerful way to respectfully depict the murder of Emmett Till," Powell said, for instance.

Till was a 14-year-old boy brutally killed in Mississippi for allegedly whistling at a white woman. His murder received national attention and helped galvanize the civil rights movement. In the graphic novel, we see an image of Till's mangled body, drawn from above, after Till has been dragged from the river. Powell makes thin jagged lines of ink to create a sense of human flesh that's turned into broken twigs.

Lewis says, just like the Martin Luther King comic book that inspired him, March is also a primer on nonviolence. The congressman says this is a lesson he and his co-authors, Aydin and Powell, want to keep alive.

"I remember hearing Martin Luther King Jr. preach from time to time," says Lewis. "And his father would be in the pulpit. And he would say, 'Son, make it plain, make it plain.' So, between Nate and Andrew, they made it plain."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.